History of the Yo-Yo - Valerie Oliver

It seems that humanity has always been captivated by the simple yet profound elegance of the spinning top. There’s something magical about how a mere flick of the hand can send it spinning, defying gravity, balanced delicately on its tip. Like many of humankind’s inventions that seem to mirror nature, there is no singular moment in time we can point to and say, “This is when the top was invented.” Its discovery or invention appears to have happened simultaneously and independently across the world, cropping up in different regions, entirely unconnected by trade or communication. Regrettably, we can’t attribute the invention of the top to any one individual, culture, or even geographical location.

The dictionary defines a top as “a child’s toy shaped like an inverted cone, with a point at its apex upon which it spins, usually activated by unwinding a string.” Yet, this definition barely scratches the surface of what tops have meant throughout history. In many cultures, they were not mere children’s playthings. In ancient Malay, for instance, top-spinning was a revered sport for adults, with tops weighing as much as 15 pounds. In Borneo and Java, their size and craftsmanship ensured that tops were reserved for adult use. Among Pacific Islanders, tops held spiritual significance. In medieval Europe, parish tops would often be found in town squares, inviting all to join in the fun. Meanwhile, in Japan and China, adult entertainers such as jugglers and top-spinners earned respect and admiration for their skill.

At its core, the essence of a top is simple: an object spinning on a single point. But this too can be expanded. A gyroscope, for example, is technically a top, though it spins on two points. Even a bullet, as it whirls through the air, mirrors the top’s motion—despite having no point of support at all. Perhaps a more fitting definition of a top, then, would be “any object that spins on a major axis.”

The likelihood is that the top was not invented once but many times, independently, by various cultures. As noted by D.W. Gould in his work *The Top: Universal Toy, Enduring Pastime*, if the transfer of simple ideas like the top had been possible across continents, there would surely be evidence of more critical inventions being shared among ancient peoples, but there isn’t. Tops have been discovered on every continent except Antarctica, and although they were often used for “play,” their origins may lie in nature itself, or in survival techniques recognized across the globe.

The acorn, with its symmetrical, conical shape, is a perfect natural top, easily set spinning by the wind. Likewise, the fluttering, spiraling descent of maple seeds could have inspired early human imaginations. Seashells, like the ones pictured here, serve as another natural spinning object, likely discovered in coastal areas. In Japan, an ancient game called “bai” or “bei” used shells as tops, experimenting with weight by filling the shells with wax or sand to enhance their spin.

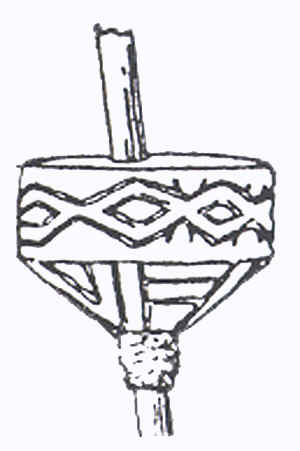

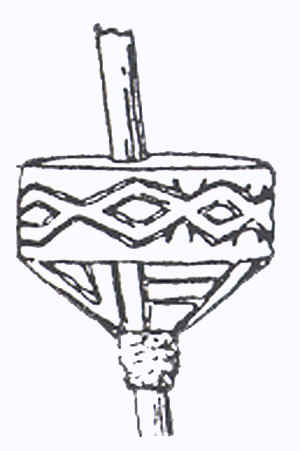

Tools for survival may have also birthed the top. Fire drills, used by primitive peoples to generate friction and spark flames, relied on the rotation of a pointed object. Such devices could have easily led to the development of spinning toys. Another precursor is the spindle whorl, defined as “a flywheel on a spindle for regulating the speed of a spinning wheel.” Spindle-whorls, discovered at archaeological sites like Troy in Turkey and in pre-Columbian Peru, were used to gather fibers and may have naturally evolved into spinning tops by the addition of a disc. Early tops from the Torres Straits in the Pacific Islands demonstrate this evolution clearly. Primitive twirlers, often crafted from seeds, fruits, or nuts with a thorn or stick through their center, represent humanity’s early experiments with spinning motion.

The top, in its simplicity, spans time and cultures. From plaything to spiritual symbol, it’s a reminder of how something as small as a spinning object can connect us all to the timeless wonder of movement and balance.

ARCHEOLOGICAL FINDINGS AROUND THE WORLD

Archeology offers us profound insights into the history of spinning tops, uncovering not only their place in different cultures but also their connection to ancient rituals, play, and craftsmanship. Through these discoveries, we witness the timeless appeal of a simple toy that transcends borders, time, and societal roles.

- In the ancient city of Ur, a remarkable find dates back to 3500 B.C., where clay tops were uncovered. Ur, known today as Muqayyar, is located about 187 miles southeast of modern Baghdad, Iraq. These delicate clay artifacts reflect the early human fascination with motion and balance.

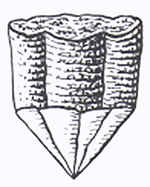

- In 3000 B.C., archaeologists discovered ceramic spinners made of terra cotta at the famous site of Troy in present-day Turkey (figure 7). These spinners not only survived the test of time but also hint at their role in the everyday lives of Troy’s inhabitants, possibly even in rituals or games.

- Traveling to Egypt, between 2000-1400 B.C., we find wood-carved whip tops (figure 8), a testament to the skilled craftsmanship of ancient Egyptians. Their wooden nature suggests that these toys were readily accessible, but their use could have ranged from simple entertainment to symbolic meanings.

- China also holds a key piece of the top’s history, where whip tops were discovered from 1250 B.C.. These ancient Chinese tops highlight the spread of this toy across Asia, revealing that play and dexterity with tops had cultural significance in this region as well.

- In Thebes, Greece, archaeologists unearthed fired clay spinning tops dating back to 1250 B.C. These artifacts signal the importance of this simple toy in ancient Greek society, possibly extending beyond mere amusement to symbolic or religious purposes.

- Around 500 B.C., Greek pottery (figure 9) painted with scenes of top spinning—both whip (figure 10) and twirler (figure 11) varieties—provides vivid depictions of life in ancient Greece. Notably, some illustrations show women playing with tops, a rare glimpse into the activities enjoyed by both genders. These tops, particularly the ceramic ones, may have been used to honor the gods as votive offerings or as symbols of status, occasionally placed in tombs to accompany the deceased into the afterlife.

- Finally, Roman tops crafted from bone, dating to 27 B.C., have also been discovered. The use of bone hints at a combination of durability and value, suggesting that Roman children and possibly even adults cherished these objects, which carried on the tradition of top spinning across cultures and centuries.

Historical Mention of Tops in Literature

The top, a simple yet enduring toy, has spun its way through the fabric of human history, leaving its mark on the literature of ancient and classical cultures. This small object, often overlooked in its simplicity, seems to evoke a certain wonder and mystery, as if it carries within its whirling motion a reflection of the cyclical nature of life itself.

Homer’s Iliad (800 B.C., Ancient Greece)

One of the earliest mentions of a top in classical literature can be found in The Iliad, where Homer uses the image of a spinning top to describe a staggering warrior, struggling at the edge of defeat:“…reels like a top staggering to its last turnings.”

This metaphor, buried within the grand narrative of Troy’s fall, adds a surprisingly human touch, comparing the final moments of a mighty hero to the delicate, inevitable end of a child’s toy’s spin.Plato’s Republic (360 B.C., Ancient Greece)

The philosopher Plato also drew upon the image of a top to explain a concept in Republic. In discussing the nature of motion, he illustrates:“A wheel or top which moves upon a fixed axis or center may be said to move or not to move, i.e., it may move at its circumference, while its axis stands still.”

Plato’s use of the top becomes a metaphor for deeper philosophical musings about change and constancy, embodying the paradox of movement and stillness.Aristophanes’ The Birds (414 B.C., Ancient Greece)

In The Birds, the comedic playwright Aristophanes references the top twice, bringing levity and playfulness to his work:“You get the idea. I’m busy as a top.”

And again: “Top? Here’s something to make tops spin.” (picking up a long whiplash)

The top, a symbol of both activity and idleness, is humorously tied to the chaotic energy of human endeavors.Virgil’s Aeneid (19 B.C., Roman Empire)

In The Aeneid, the Roman poet Virgil offers one of the most vivid and detailed descriptions of a spinning top in ancient literature:“Beneath the twisted whips a leaping top,

Sped in long spirals through a palace-close

By lads at play; obedient to the thong,

It weaves wide circles in the gaping view

Of its small masters…”

Virgil paints a picture of children controlling the wild motion of the top with their whips, marveling at how it dances through the air—a living, vibrant thing under their command.St. Basil’s Hexamer (365 A.D.)

Moving forward into early Christian literature, St. Basil uses the top as a metaphor in his theological writings:“Like tops which, as a consequence of an initial impulse, orient themselves and spin on their axes…”

In this comparison, the spinning top becomes a symbol of the natural order of the universe, reflecting the idea of divine motion and purpose.Shakespearean References (1564–1616 A.D., England)

The top also found its way into the works of Shakespeare, who used it as both a metaphor and a symbol of childhood in various plays:- Merry Wives of Windsor: “…played truant, and whipped top…”

- Winter’s Tale: “…not big enough to bear a school boy’s top…”

- Coriolanus: “…turned me about with his fingers and thumb, as one would set up a top…”

- Twelfth Night: “…turn o’ the toe like a parish-top…”

In these lines, Shakespeare uses the top to describe characters’ behaviors, often drawing on the image of spinning or turning to signify confusion or rapid movement.

Types of Tops

Throughout history, the evolution of tops has given rise to a variety of forms, each differentiated by the way they are spun. The diversity of tops is not a reflection of a linear development, but rather a testament to the creativity and cultural significance of the toy across different societies.

Twirler:

This top is spun by twisting the stem with one’s fingers or hands. It is one of the simplest and oldest forms, appearing in many cultures worldwide. A common variant, the “teetotum,” is a top with four lettered sides used in games of chance. For example, in European countries such as Germany, Poland, and Scotland, children played games to see how many tops could be kept spinning simultaneously. In Japan, however, tops are not just toys for children—they are respected objects used by entertainers and jugglers. The Japanese “spindle top” (figure 17), with its long, thin stem, is renowned for its artistry.Supported Top:

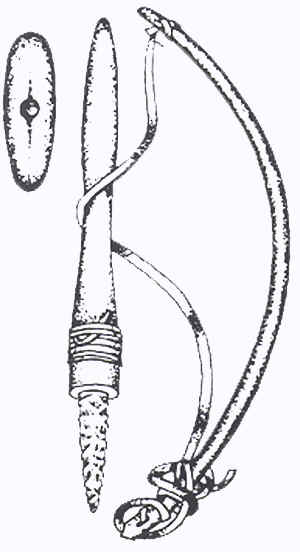

This top is spun by pulling a cord while the top remains upright, typically supported by some structure. The design and function vary, but the principle of continuous motion driven by external support is the defining characteristic.Whip Top:

A whip top relies on continuous whipping to maintain its spin. This type was often seen in both playful and ceremonial contexts, where skill and precision in controlling the top were admired.Throwing Top:

In this form, a cord is wrapped around the body of the top, which is then thrown to initiate spinning. The act of throwing, combined with the pull of the cord, generates a powerful and sustained motion.

One remarkable type of top is the Japanese iron-clad top, or “tetsudo.” Featuring a metal ring around its wooden body, this top is designed for extended spins due to its enhanced weight distribution. Skilled performers can balance it on various surfaces, including the edge of a sword, showcasing a deep cultural appreciation for the art of top-spinning.

In the realm of modern ingenuity, the tippee top stands out for its unusual behavior. Patented in 1953, this top initially spins as expected, but when spun swiftly, it flips over and continues spinning on its peg. The phenomenon of the top inverting itself has baffled both physicists and mathematicians alike.

Tops, in their many forms, remain more than mere playthings. They are testaments to the boundless curiosity and creativity of humankind, a spinning thread that connects past to present.

2. Supported Top

- A marvel of simple yet ingenious design, spun into motion by a cord while balanced upright on a support.

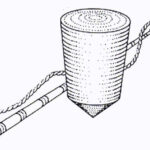

As ancient hands first twisted these early tops, they quickly learned that the amount of spin was limited to the dexterity of their fingers. It wasn’t long before inventive minds sought a solution. By wrapping a string or rope around the stem and giving it a good, forceful pull, they found that the top could spin faster and longer. But there was a problem—how to keep the top steady while pulling the cord? The challenge sparked even more creativity.

Early inventors crafted handles or brackets, sometimes from wood or even hollowed shells, to hold the top upright. With one hand gripping the handle and the other pulling the cord, they could set the top spinning with a speed and precision previously unimaginable. As soon as the top twirled into motion, the handle would be lifted away, leaving the top dancing freely on its own momentum.

In time, variations emerged. One clever design tied the cord directly to the top’s axis. When pulled, the top spun into life, but instead of stopping when the cord unwound, inertia would cause the cord to wind itself back up in the opposite direction. This allowed for continuous, rhythmic pulls—each one reversing the spin, creating an entrancing, perpetual motion.

Even today, modern toys like the gyroscope echo this ancient principle. A metal frame, much like the early handles, surrounds the spinning disk, giving structure and balance while the internal forces create seemingly impossible motions. It’s a reminder that even the simplest of toys can connect us to the ingenuity of our ancestors, their desire to solve problems, and their endless fascination with motion.

3. Whip Top

- A spinning toy propelled by whipping, creating continuous motion.

Whip tops, ancient toys with a surprising endurance through the ages, have roots tracing as far back as 2000 B.C. in Egypt and 1250 B.C. in China. However, the first formal written record of whip tops appears in 1344 A.D., in a French manuscript titled Roman d’Alexandre, with more frequent mentions surfacing in the 18th and 19th centuries. The whip top, much like a shared piece of human creativity, spread far beyond any single culture. From Europe to the Americas, from Northeast Asia to the Pacific Islands, and even as far as India and Africa, this simple toy carved its place in history. Some sources attribute its invention to China, from where it was allegedly introduced to Europe by seamen who had encountered it on their travels. Yet, it seems the whip top developed independently in various regions, such as Egypt, a phenomenon seen in many societies where similar inventions emerge without any direct connection, mirroring the way some contemporary indigenous tribes create tools without external influence.

The design of the whip top is elegantly simple. Most were shaped like cones and crafted from wood, clay, or occasionally stone. In the 18th century, particularly heavy iron whip tops were made for spinning on frozen ponds and lakes, where the durability of the peg was less of a concern, as the icy surface reduced wear. Any imbalance in their construction became irrelevant, as the continuous whipping action helped the top maintain its spin regardless of imperfections.

The magic of the whip top lies in its movement, achieved by vigorously whipping its sides to keep it spinning. The material of the whip was just as crucial as the top itself. Europeans favored eelskin for its softness and resistance to cracking, while other cultures in America, Asia, and more remote regions opted for alternative skins, woven cords, or fabrics.

Socially, the whip top stands out from other types of tops. In ancient Greece, top spinning was a pastime enjoyed by both boys and girls, as depicted in various pottery carvings and paintings. However, in the Pacific Islands and Southeast Asia, the whip top became largely a male-dominated activity, with women and girls rarely participating. Similarly, in European cultures, women were seldom seen playing with tops. Despite this, there were notable exceptions, like in England, where whip top spinning was specifically listed as an acceptable form of play for students at Harrow School in 1591. The school’s “Orders, Statutes, and Rules” stated:

“…The scholars shall not be permitted to play, except upon Thursday only sometimes when the weather is fine, and upon Saturday, or half-holidays after prayer. And their play shall be to drive the top, to toss a handball, to run, or to shoot, and none other.”

The phrase “to drive the top” referred explicitly to whip tops, marking them as a wholesome and affordable way to stay active.

Perhaps the most curious example of the whip top’s social significance is the parish top, a much larger and heavier variant believed to have been used not only for amusement but also to encourage physical exercise or foster friendly competition between towns. Although no original parish tops are known to have survived, historical drawings depict them as substantial, often around 8 inches tall and weighing at least 2 pounds. Such a large top would have required great strength and stamina to keep it spinning, with multiple adults sometimes working together to whip it into motion. It’s even been suggested that in colder climates, this physically demanding activity was a practical way to stay warm during the winter months.

4. Throwing Top

The throwing top, often mistakenly called a “peg top,” offers a unique form of play that merges precision and skill. The name “peg top” is actually a bit misleading—traditional peg tops were carved to a point, but didn’t feature an inserted peg. The throwing top, in contrast, has a pear-like shape with a pointed end, and it’s set into motion by winding a cord around its body and tossing it to unwind, resulting in a spinning motion. Although no evidence suggests that throwing tops were used in classical times, they have been crafted by various cultures, notably in Malaysia and Japan.

Among all types of tops, the throwing top offers the most diverse forms of play. It’s not just a toy but a test of skill, making it the only top whose performance can be measured and even used in competitions. Some historians speculate that the throwing top evolved from the whip top, a game that required more strenuous effort. Others credit Japan as the birthplace of the throwing top, although specific details remain elusive. Regardless, it’s widely accepted that Japan and other Northeast Asian cultures introduced the technique of spinning tops with strings.

The earliest throwing tops were likely made of wood, with grooves carved into the body to secure the cord more effectively. Originally, the pointed tip was simply an extension of the top itself, but over time, artisans began incorporating harder materials like bone or even metal for added durability. The insertion of a small nail or brad into the tip allowed for better balance and longer spin times. A well-balanced top was crucial—an off-balance top would wobble and lose its momentum. As craftsmanship improved, the peg at the tip became smaller, reducing friction and allowing for faster, more stable spins.

Throwing tops weren’t just a test of skill; they were also used for competitive games. Players would attempt to outspin each other, knock other tops out of a target area, or even split an opponent’s top in two. One of the most memorable variations involved wooden tops with nail points, popular in top-fighting games. In these contests, players aimed to strike their rival’s top, trying to break it apart.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, tops were a beloved pastime for children in both Europe and America. Whip tops and peg tops were particularly popular, as evidenced by woodblock prints from the era. These early tops were made from materials like wood, iron, and tin, reflecting the craftsmanship of the time.

Methods of Throwing a Top

Throwing a top is an art in itself, with numerous techniques depending on the shape of the top and the preference of the player. There are several ways to wind the string around the top, and just as many ways to release it. As the top is thrown, the string unwinds, causing the top to flip over until it lands with the point down, spinning upright. Factors such as the string’s length and thickness, the top’s shape, and the mechanics of procession all influence how well the top spins.

The Wind

Figure A: In early models, the string was wound along the side of a rounded top, with one end extended down to the tip and then wrapped over itself. The button at the end of the string was secured behind the hand, held between two fingers. When released, the string remained caught between the fingers, allowing for a smooth unwind.

Figure B: Later versions of the top featured a groove at the upper end where the knot of the string could be secured. The string was then extended down to the tip and wrapped upward.

Figure C: By the 20th century, some tops had cap edges that allowed the string to be wrapped around the cap and locked in place with a knot. The string was then extended down to the point and wrapped upward, ensuring a tight and secure wind.

The Hold

Once wound, tops can be held and thrown in various ways. Some players prefer to hold the top upright, while others hold it sideways before releasing it. Since the 1960s in the United States, the most common method has been to hold the top upside down, with the point facing upward before the throw.

The Throw

There are several ways to throw a top, each offering a different level of speed and accuracy:

Underhand Throw: The top is tossed with an upward flip of the hand. While this method is simple, it lacks precision and results in a slower spin.

Overhand Throw: This method increases both speed and accuracy. The motion resembles throwing a ball but is directed downward, producing a faster, more controlled spin.

Side Throw: The top is held upside down with the point facing up, and the arm is swung forward in a motion similar to throwing a disc. This method significantly improves accuracy, allowing skilled players to hit precise targets, such as a bottle cap.

Recent History of the Throwing Top

In the 1960s, a cultural revolution swept across the United States, and, amidst that, the humble throwing top made its grand return to the spotlight. Duncan Toy Company, known for popularizing the yo-yo, began a campaign to bring spin tops to the masses. Like the yo-yo, they used expert demonstrators who traveled from city to city, captivating audiences with tricks and techniques that breathed new life into this ancient toy.

Initially, these tops were crafted from wood, painted either by hand or sprayed with machines, reflecting the craftsmanship of the time. But as the years rolled on, plastics entered the fray. Companies like Duncan, Festival, and Royal began producing plastic tops, and they were a game-changer. These hollow plastic tops spun longer than their wooden counterparts, as their design distributed mass to the outer edges, maximizing stability and duration of the spin.

In 1963 and 1964, Duncan sponsored regional championships, culminating in a grand National Spin Top Competition at Disneyland in California. The prize? A life-changing $5,000—a fortune for a young player in the mid-60s. The top champions of the era—Pete Span, Forest Larson, and Bob Donna—etched their names into history. Yet, the joy was short-lived. In 1965, Duncan filed for bankruptcy, and with that, the competitions disappeared, leaving just two glorious years of national top championships.

Fast forward to 1991, at the International Jugglers Festival, where a new generation of top enthusiasts was born. Don Olney from The Toycrafter in New York held a workshop that reignited the love for spinning tops. Attendees, many of whom had played with tops in the 1960s, flocked to the event. Among them were Dale and Valerie Oliver, seasoned top players who shared their knowledge with a new, eager audience. That same year, Japanese master Masahiro Mizuno stunned the crowd with his intricate tricks, showcasing the elegance of Japanese tops and fueling a global resurgence of interest in this ancient toy.

By 1999, spin tops were once again gaining traction in the commercial world. Spintastics Skill Toys and What’s Next Corporation launched their lines of tops, promoting them through demonstrations, just as Duncan had done decades earlier. Duncan, now owned by Flambeau Products, re-entered the market, joined by other companies like Moose of Australia and YoYoJam in the United States. The year 2000 marked a major milestone, as the first spin top contest since the 1960s was held at the World Yo-Yo Competition in Orlando, Florida. From there, the momentum only grew, with the National Spin Top Contest officially returning in 2002—nearly four decades after its abrupt disappearance.

In 1995, a new innovation changed the landscape of top spinning: the ball-bearing top, designed by Dale Oliver. Introduced by Spintastics Skill Toys in 1999, the Tornado Top allowed for much longer spin times by reducing friction between the point and the surface. This revolutionary design opened the door to a whole new world of tricks. Yet, while ball-bearing tops offered new possibilities, fixed-tip tops remained essential for certain tricks that required friction between the tip and the string.

The double-tip top, another breakthrough, was invented by Luis Borge and released by YoYoJam in 2000. This unique design featured spinning points at both the tip and the cap, further expanding the possibilities for top players.

Variations of the Top

Buzzer – A classic toy, spun by twisting a cord that creates bi-directional motion. Though not shaped like a traditional top, it spins on its axis and has appeared in almost every ancient culture, from classical Greece to primitive Africa. Known by many names—whizzer, mow-mow, magic wheel—it produces a mesmerizing hum as it spins. Its enduring appeal lies in its simplicity, using a string and a disc to create a charming toy that has entertained generations.

Yo-Yo – Perhaps the most famous tethered top, using inertia and kinetic energy to keep it moving. For more details, refer to Yo-Yo History.

Diabolo – A spool spun on a string between two sticks, originating in China. It gained popularity in Europe after being introduced by missionaries, and by 1907, Parker Bros. brought it to the U.S. market.

Pump Top – Driven by a plunger that creates a spinning motion. Successive pumps keep the top going, often enhanced with music or lights for added fun.

Spring Top – A 19th-century invention, featuring a spring-loaded cap that, when released, spins the top. Though few survive today, these delicate toys once captivated children with their metal or plastic bodies.

Magic or Silhouette Top – These unique tops cast shadows in the shape of a face when spun. Popular in 18th-century France, one famous example features the profile of King Louis VI, and another from 1790 depicts Marie-Antoinette.

Wizzer – A product of the 1960s, this top by Matchbox had a friction motor activated by sliding the tip along a surface. It gained a cult following, with similar versions from other companies, including Duncan.

Aeolian Top – A 19th-century wind-propelled top named after the Greek god Aeolus. By blowing into its center, users could watch the top spin effortlessly.

Whistler/Humming Top – Designed with holes to produce a sound while spinning. The first U.S. patent for a top was granted in 1854 for a whistling top.

Double Top / Twin Top – A nested top that splits apart when spun, adding an element of surprise and fun to traditional spinning.

Magnet Top – A top with a magnetic cap that allows it to hang and spin from a metal ring worn on the finger.

Chain Top – Featuring a chain or string attached to its cap, which releases the top when spun, creating a dynamic and unpredictable play experience.